The world is currently faced with the emerging epidemic of cardiometabolic disease but early screening for symptoms that commonly present with new-onset cardiovascular risk can assist with patient risk stratification and health management protocols.

The global prevalence of metabolic syndrome differs depending on geographic and sociodemographic factors. It is estimated that in the United States 35% (50% of adults >60) were diagnosed with metabolic syndrome (30.3% in men and 35.6% in women).1 In Europe its prevalence has been estimated at 41% in men 38% in women.2 The Middle East reports a prevalence of 20.7-37.2% in men and 32.1-42.7% in women.3 Data from China suggest a 58.1% prevalence in the 60 and older age group.4 In Africa the prevalence of metabolic syndrome is estimated between 17-25% in the general population.5

The metabolic syndrome, syndrome X or “the deadly quartet” is characterised by a cluster of risk factors including abdominal obesity, hyperglycaemia (insulin resistance), hypertension, and dyslipidaemia (high levels of triglycerides, and low levels of high-density lipoproteins).6,7 These factors raise the risk of developing type 2 diabetes, atherosclerotic cardiovascular diseases, hyperuricemia/gout, chronic kidney disease, obstructive sleep apnea, and neurological complications such as cerebrovascular accident due to chronic inflammation and endothelial dysfunction.7,8

Metabolic syndrome is clinically defined if the patient has any three9 or more of the following:

- Waist circumference > 102 cm in men or > 88cm in women.1

- Elevated triglycerides 1.7 mmol/L

- Reduced high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL) less than 1.0 mmol/L in men or less than 1.2 mmol/L in women

- Elevated fasting glucose of 5.6 mmol/L or greater

- Blood pressure values of systolic 130 mmHg or higher and/or diastolic 85 mmHg or higher (Note that SBP 140 mmHg is Hypertension)

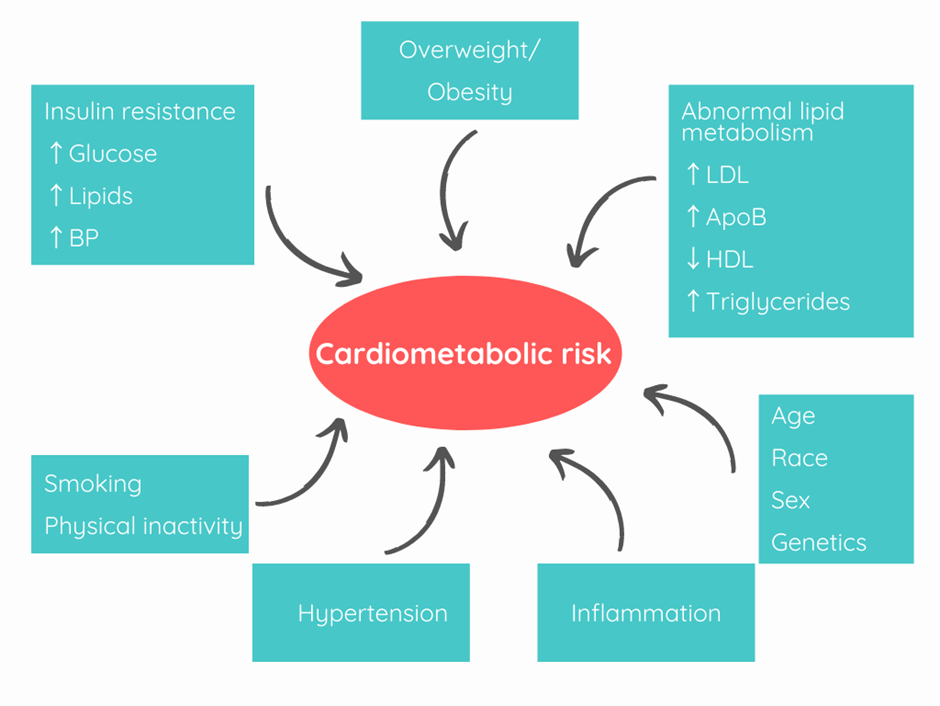

ApoB: Apolipoprotein B; BP: Blood pressure; HDL: High-Density Lipoprotein; LDL: Low-Density Lipoprotein.

Pathophysiology

The crux of the syndrome is a build-up of adipose tissue, subsequent tissue dysfunction and inflammation that in turn leads to insulin resistance that adversely influences several physiological systems (Figure 1).

Abnormal lipid metabolism:

An increase in small dense LDL particles and ApoB, low HDL cholesterol, and elevated triglycerides are characteristic of lipoprotein abnormalities. Enlarged adipose tissue releases proinflammatory cytokines such as tumour necrosis factor, leptin, adiponectin, plasminogen activator inhibitor, and resistin which leads to insulin resistance and atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis leads to the development of plaques that obstruct normal blood flow. Plaques can rupture or erode, leading to blood clots that can lead to clinical complications such as myocardial infarction and stroke.10

Insulin resistance:

Impairment of the signalling pathway, insulin receptor defects, and defective insulin secretion can all contribute to insulin resistance and hyperglycaemia. Insulin resistance causes microvascular damage, which predisposes a patient to endothelial dysfunction, and hypertension.11

Hypertension:

Hypertension, in turn, leads to increased vascular resistance and stiffness causing peripheral vascular disease, ischemic heart disease and renal impairment.

Prevention is better than cure

It is time to tackle the risks of its development at an earlier stage in our communities. This starts with identifying those at risk of developing cardiovascular diseases (CVD), pre-diabetes, diabetes, and fatty liver diseases.

In high-income countries, substantial progress has been made in the prevention and treatment of cardiovascular diseases. However, simultaneously the prevalence of obesity and type 2 diabetes are on the rise and driving comorbidities.12

Early screening for risks

Some recent advances in risk screening have helped to simplify the process of identifying those at higher risk of developing cardiometabolic disease.13

Non-invasive health insight through Smart devices

Recently the industry has moved towards accessible non-invasive continuous health monitoring from the comfort of your home with apps and wearables that can screen for cardiometabolic risk.14

- Measuring heart rate (HR) and heart rate variability (HRV) and blood pressure (BP) via PPG or TOI

- Glucose monitoring: fabric-based and epidermal-based electrochemical sensors for monitoring

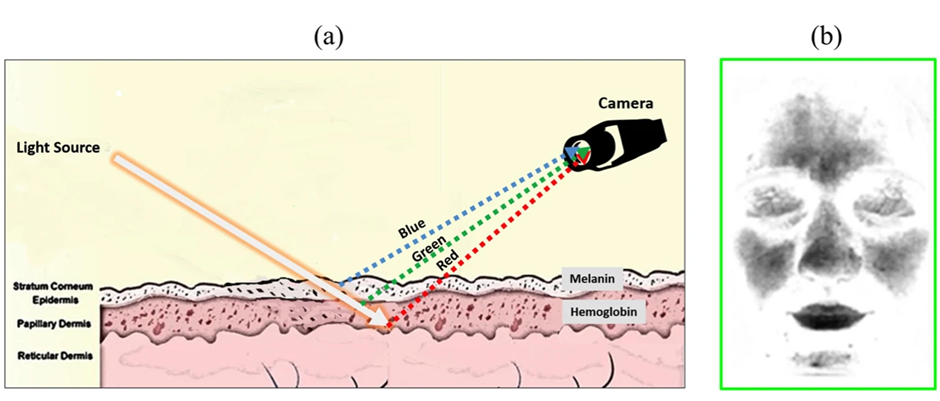

Most devices rely on using a technique called photoplethysmography (PPG) to detect blood flow rates by capturing light intensity reflected from skin based on LEDs and photodetectors against the skin usually through the phone camera.14 However, a promising technology, transdermal optical imaging (TOI) which is based on video images assessing basal stress is adding additional measurement options. This contactless technology measures facial blood flow changes using a conventional digital video camera. TOI measurements of HR and HRV, BP reflects basal stress and can be used to determine cardiometabolic risk.15,16

Online options for initial screening for cardiometabolic syndrome

• Questionnaires with risk scores for CVD based on simple questions and physical measures are now available online.

• Body mass index, waist to hip ratio, and grip strength may also aid in risk scores.

• Online diabetes risk assessments are available.

• Risk scores for liver fibrosis are now available online.

These accessible assessments can be done quickly by a range of trained professionals to inform which people require further blood testing and evaluations. It could also be done in a range of non-clinical settings that people often visit such as barbershops, pharmacies, and community centres to make initial checks more accessible.

The next steps

Risk scoring for cardiometabolic disease could take place in a three-stage process:

- The first step would be non-invasive home-based, requiring only measurement from smart devices or wearables and anthropometric measurements.

- The second step could be online risk assessments facilitated by trained professionals.

- The third step for those at elevated risk or above a certain age should be measurements for relevant biomarkers (glucose, insulin, lipids etc.) in a clinical setting.

These non-invasive preventative tactics and holistic risk assessments can help to mitigate future risk of cardiometabolic disease and offer patients evidence-based recommendations in an effective manner. The SapioSentient network is passionate about improving human healthspan and reducing the burden of non-communicable diseases and welcome further discussion on the biochemical and physiological abnormalities associated with metabolic syndrome.